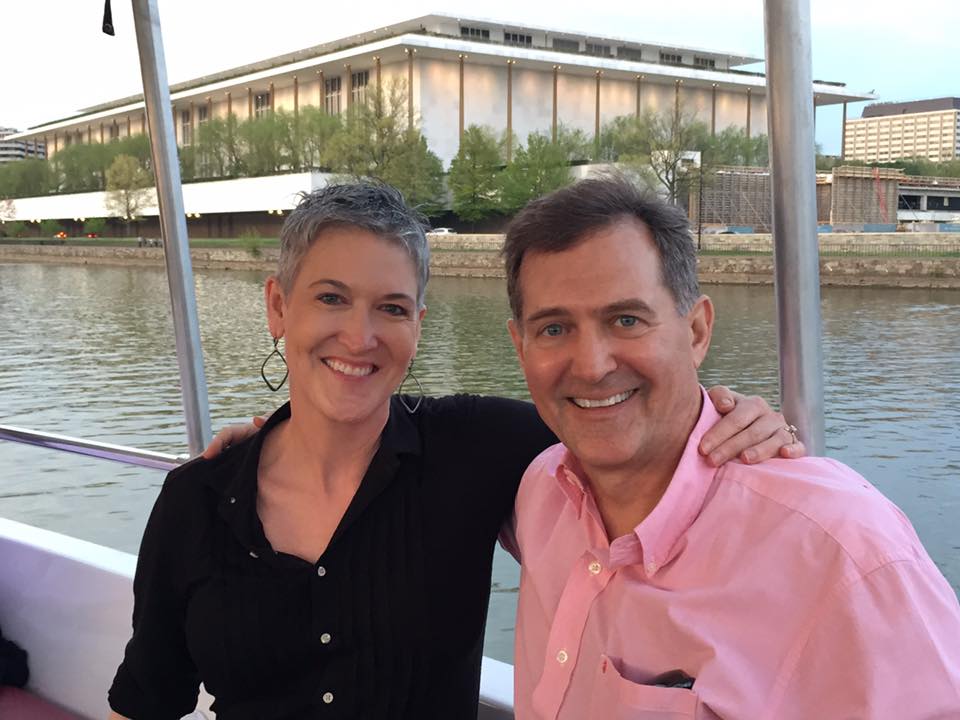

The phone call came in the middle of the night from a US military source involved in the air campaign against ISIS. It was September 2015, and Russian warplanes had refused an American request to clear the airspace in northern Syria. Bleary eyed, Jennifer Griffin, the national security correspondent for Fox News, made her way from the bed to her desk. She was too tired to go to another room, and did the interview while her spouse of 25 years, Greg Myre of National Public Radio, listened in on the scoop.

“I told Greg, ‘Go to sleep, this is off the record.’” she recalls. “I can’t remember if I told him what it was about while he was still waking from his sleep or whether he got a rocket from his office later on. I probably said, ‘Follow me on Twitter.’”

He obeyed.

Anyone who has been married for a long time knows that elasticity keeps a bond strong. Husbands and wives must compromise and agree on rules of the road. In this case, that means respecting each other’s political opinions and exclusive stories. Griffin and Myre now cover the same beat, national security, for media outlets widely perceived as being at opposite ends of the political spectrum. At a time of intense national polarization, their partnership has achieved a rare civility across the partisan divide.

Griffin interviews Hillary Clinton on a campaign plane in 2016.

They may withhold news or sources, but they are each other’s favorite sounding boards. They critique and edit each other’s stories. They bounce ideas around.

ICYMI: Eight simple rules for doing accurate journalism

“We don’t always see the world the same way, but always debate and discuss,” says Griffin. “Our relationship is better for that.”

Colleagues who know them well say the pair sets an example for us all by approaching differences with genuine interest and good humor.

“Maybe there’s a recipe for our politics in that, given the decline of debate and recent tendency among Americans, including some journalists, to brand people they disagree with as dumb or racist or PC, without a sincere effort to understand why they think or vote the way they do,” says Elizabeth Williamson, an editorial writer for The New York Times and friend of Griffin and Myre. “Seeing them together teaches a lesson we’re all prone to forget lately: Be open, ask questions, don’t take yourself too seriously. To my mind that’s what makes them admirable as journalists, and as a couple.”

Their biggest dissatisfaction is not with each other, but with the charged political environment dividing fans of their respective news organizations.

Griffin and Myre rankle at the suggestion that they are ideologically driven. They see themselves as straight-news professionals who simply report facts. Griffin stresses that she doesn’t work for the opinion shows at Fox, and notes that she freelanced for NPR before joining the network Roger Ailes founded about two decades ago.

The pair was shocked by the partisan media landscape when they returned to the States from foreign postings 10 years ago. “When we were overseas, they didn’t see you as a liberal journalist or a conservative one,” says Myre. “Now you’re pigeonholed, ‘I don’t want to talk to you because you’re not on my side.’ We find that disappointing.”

The couple met at a political rally in a crowded sports stadium in South Africa, on October 29, 1989. Griffin was a college student on break from Harvard, working for The Sowetan newspaper. Myre was a staff correspondent with the Associated Press. His phone didn’t work, so Myre went to the next press booth, where Griffin happened to be bringing popcorn to colleagues. He asked her out a few days later, and thus started a relationship that later saw postings in Pakistan, Moscow, and Jerusalem for a variety of organizations. They have three kids and wrote a book together about the Middle East.

For sure, there have been wrinkles along the way. But what marriage doesn’t have those?

Myre stands in a bombed-out MIG fighter jet during the First Gulf War.

To start, there was Griffin’s first big break in Pakistan right after they got married in 1994. She was a stringer for what she will only describe as a “big newspaper.” Myre was still with the AP. The correspondent Griffin reported to made her promise not to tell her husband what she was working on. “Macy’s doesn’t tell Gimbels,” he would say, referring to the competing department stores.

It was awful keeping secrets. “I eventually stopped working for that newspaper because there were a lot of tears,” Griffin recalls.

Having established that they shouldn’t be cloak and dagger, they then had to figure out the hotel situation. In 1995, she kicked him out of their shared room in Tehran because she was too nervous to voice pieces with him present. Myre wandered the streets angrily at night until she finished filing. “It was a sore point,” she admits dryly.

ICYMI: Here’s what non-fake news looks like

Tensions flared again in 2006, on the border of Israel and Lebanon. Griffin insisted that her beloved get a separate room because his typing interrupted her sleep, an order “he’s never let me forget.”

These days they don’t travel together unless they’re on vacation. They often exchange notes, though generally at the end of the day after stories have been filed. They even share contacts, an area where Griffin has an advantage, having covered the Pentagon longer. Myre suspects the missus holds back a little. But don’t get him wrong. “She’s been very good: ‘Here’s somebody who will be friendly, drop my name and tell them you’re my husband.’ The Pentagon is a confusing place and you have to know who to talk to. She knows all the generals.”

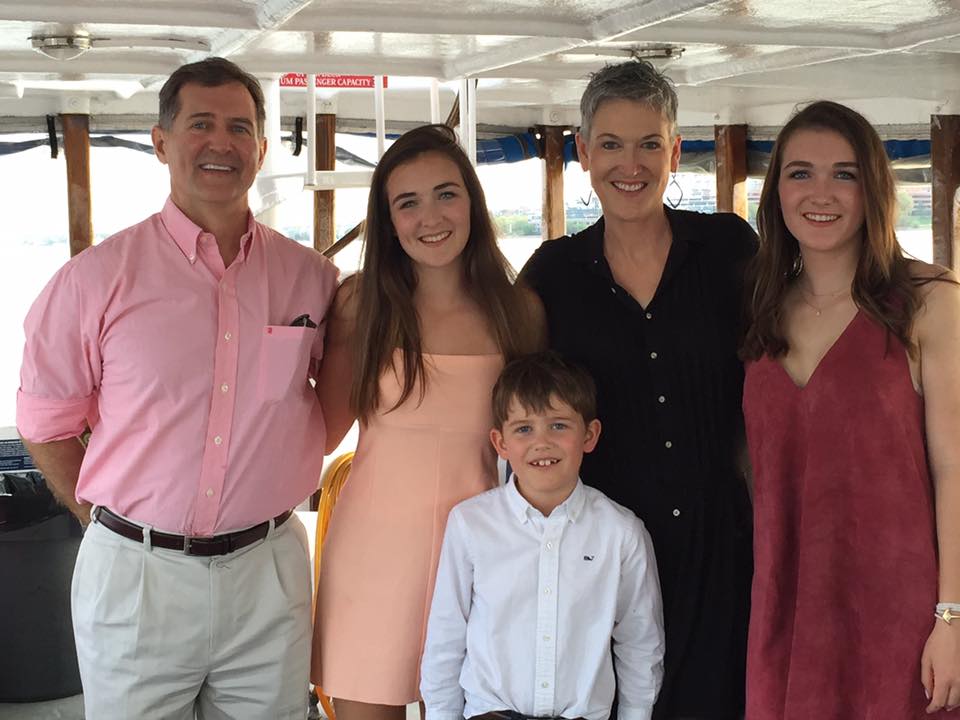

Griffin, Myre, and their three children

Their biggest dissatisfaction is not with each other, but with the charged political environment dividing fans of their respective news organizations. They’ve been at school events or dinner parties where people have turned their backs on one of the two spouses. The couple tries to laugh it off.

Sometimes it helps that their audiences are so different. Griffin does mostly breaking news emanating from the Pentagon, while Myre writes more features, reporting on Capitol Hill one day and tapping international sources the next.

While Myre says some of their most heated arguments have been around the news—“the kids’ problems can wait, we have to talk about it”—this exposure at the dinner table has given their children ringside seats to debates happening in real time. No wonder, then, that Annalise, 16, edits the school paper and Amelia, 14, writes for it. Eight-year-old Luke, meanwhile, is obsessed with military history.

While the elders say the offspring have a broad understanding of the complicated news environment, the youngsters are very much their own people who get news piecemeal through social media and friends. They don’t go out of their way to watch her or listen to him.

But when they do, which outlet do they prefer? NPR or FOX?

Griffin chuckles mysteriously. Some things are better kept in the family.

Judith Matloff teaches conflict reporting at Columbia's Graduate School of Journalism. She's the author of two books on conflict, Fragments of a Forgotten War and No Friends But the Mountains, as well as a manual for journalists covering dangerous stories, How to Drag a Body.